Self-Improvement Books

Self-Improvement Books

The Art of Memoir

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

From Strength to Strength: Finding Success, Happiness, and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

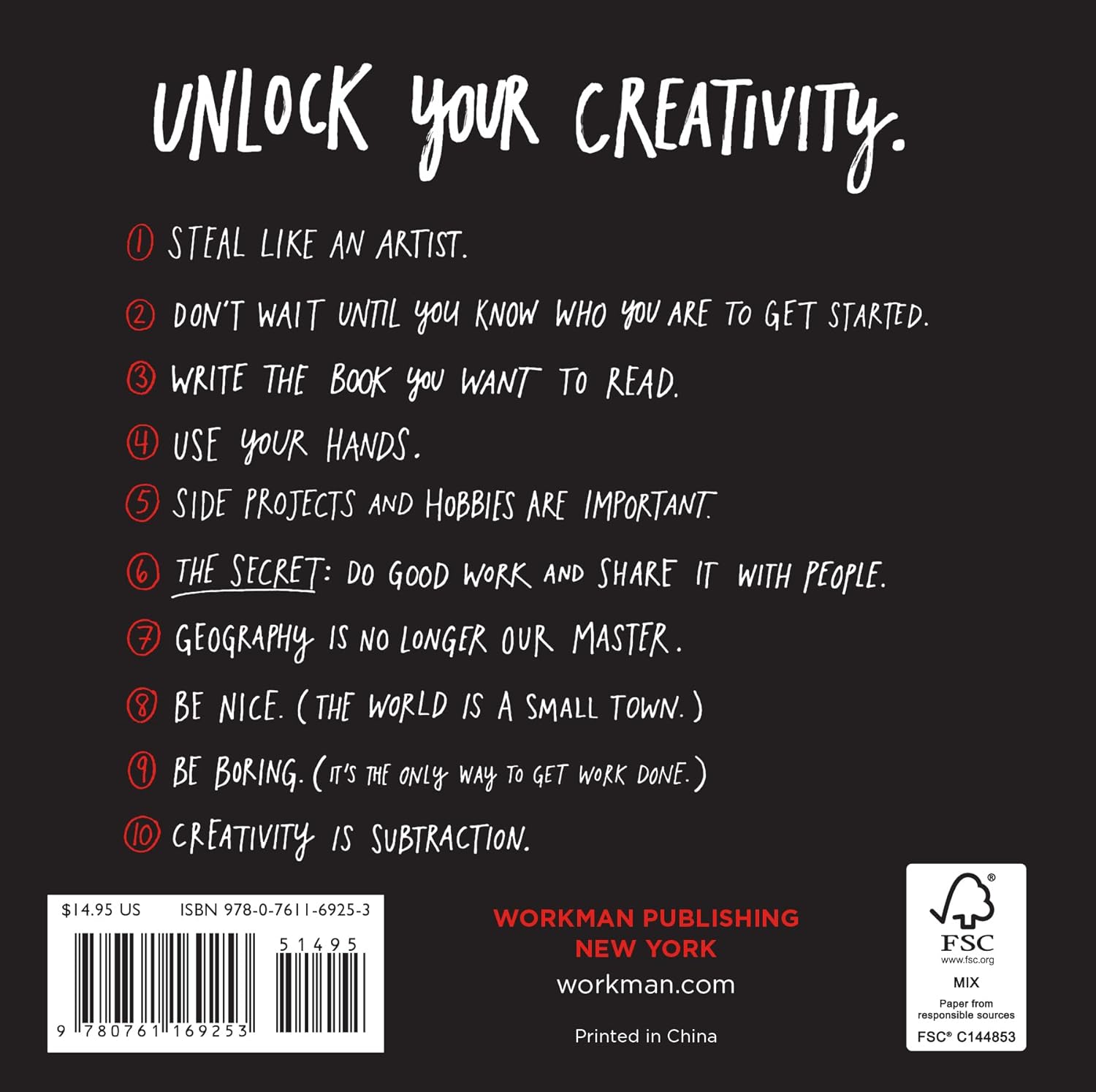

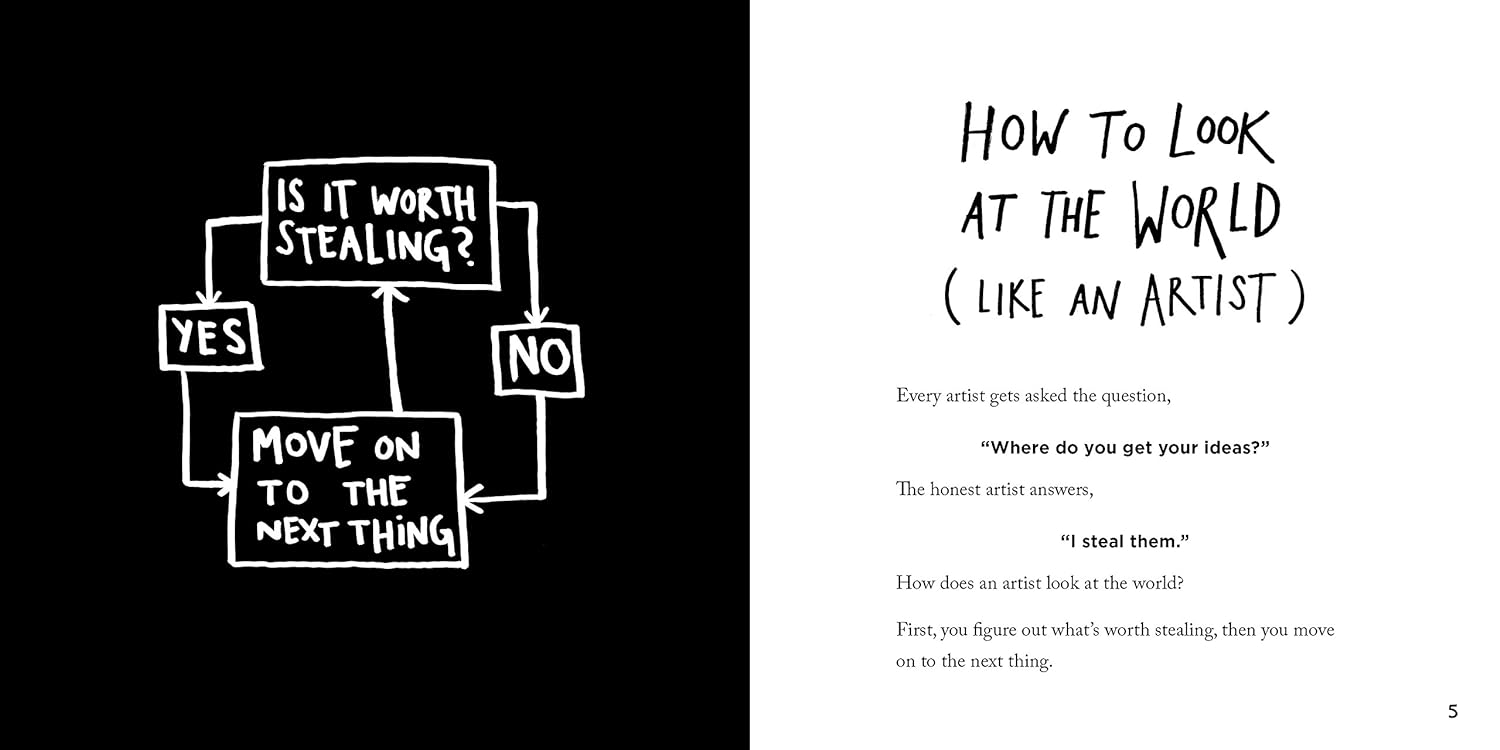

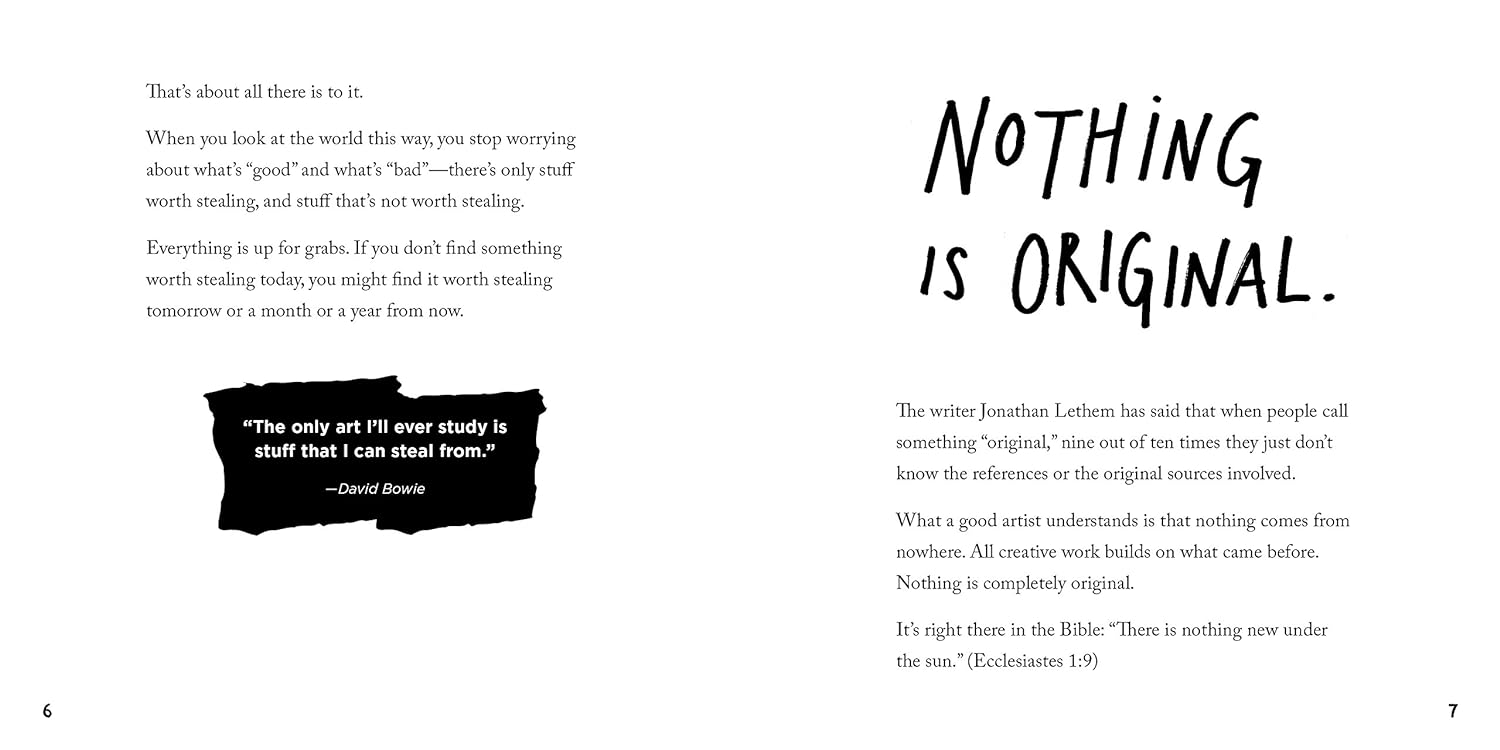

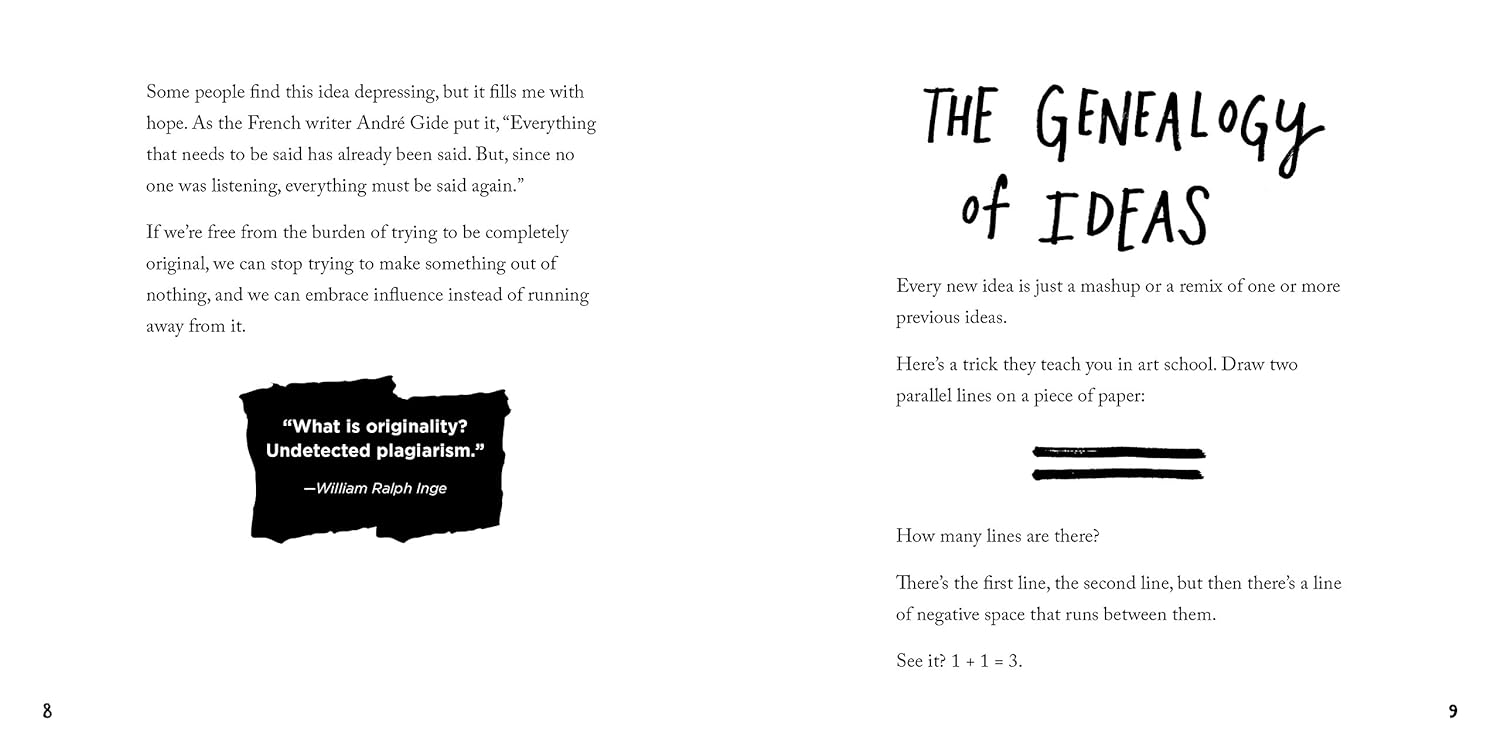

Steal Like an Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

[By Mo Gawdat ] Solve For Happy: Engineer Your Path to Joy

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Filmmaker Says: Quotes, Quips, and Words of Wisdom

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

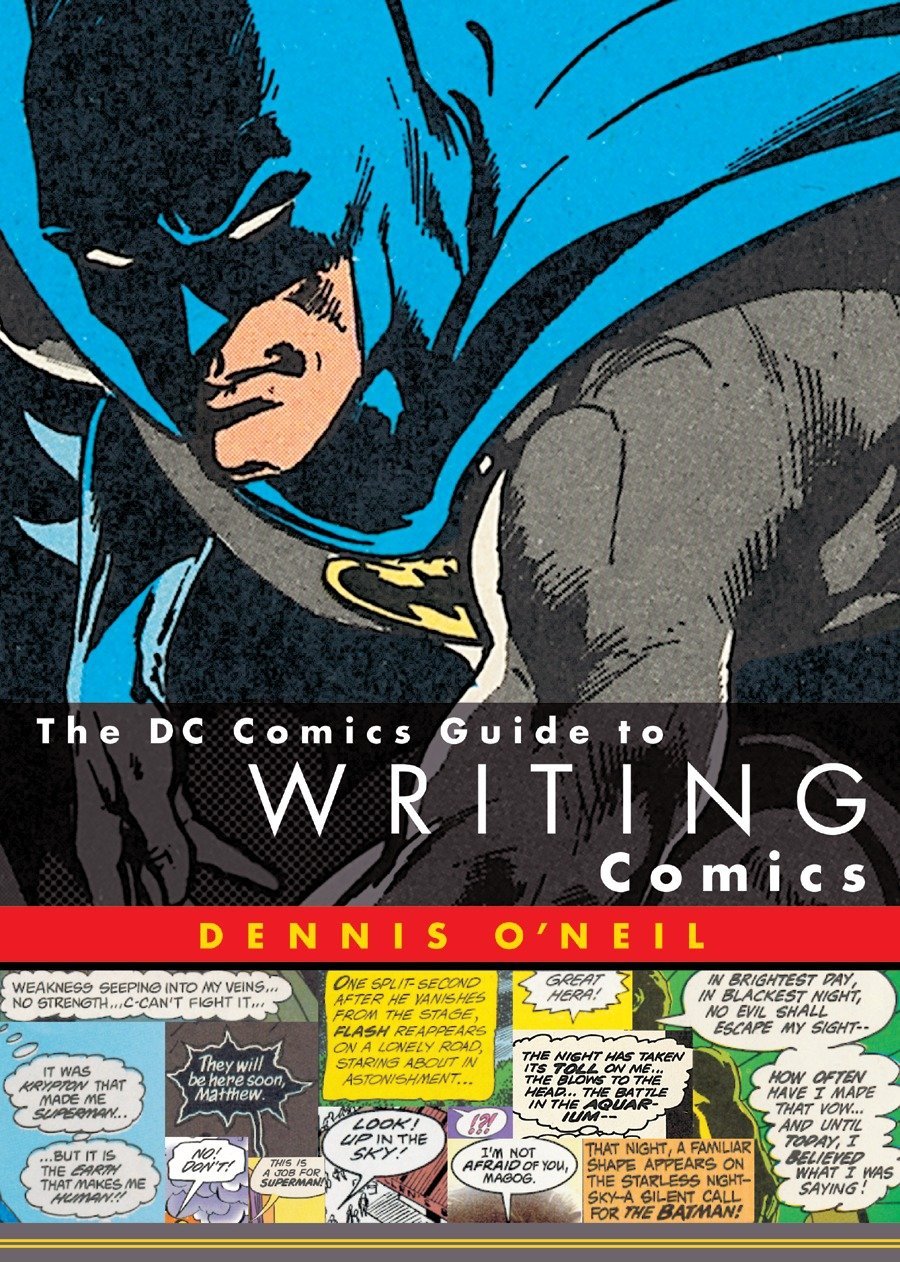

The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Artists' Prison

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

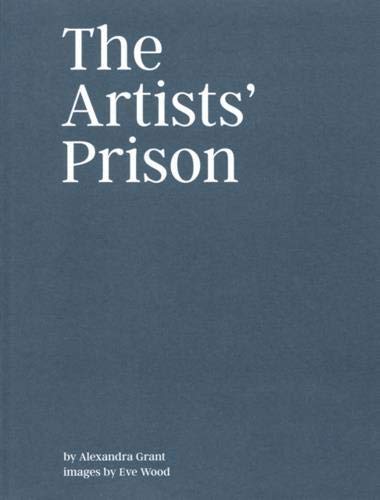

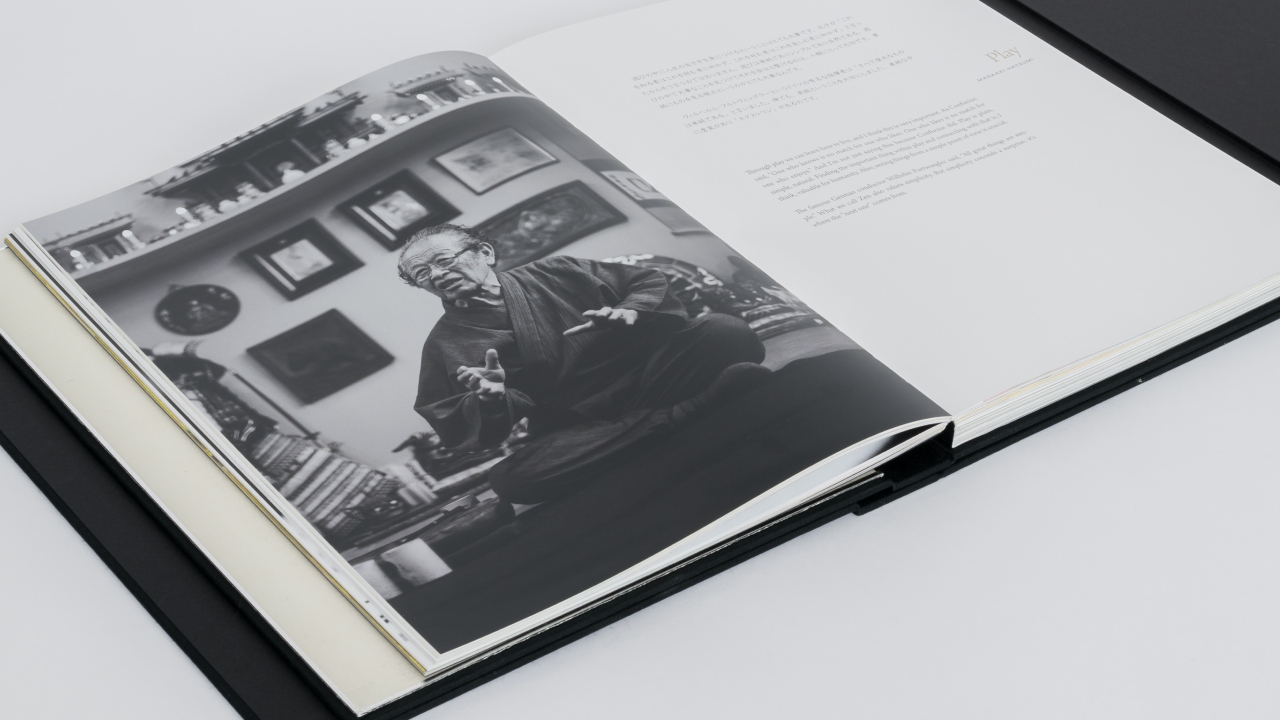

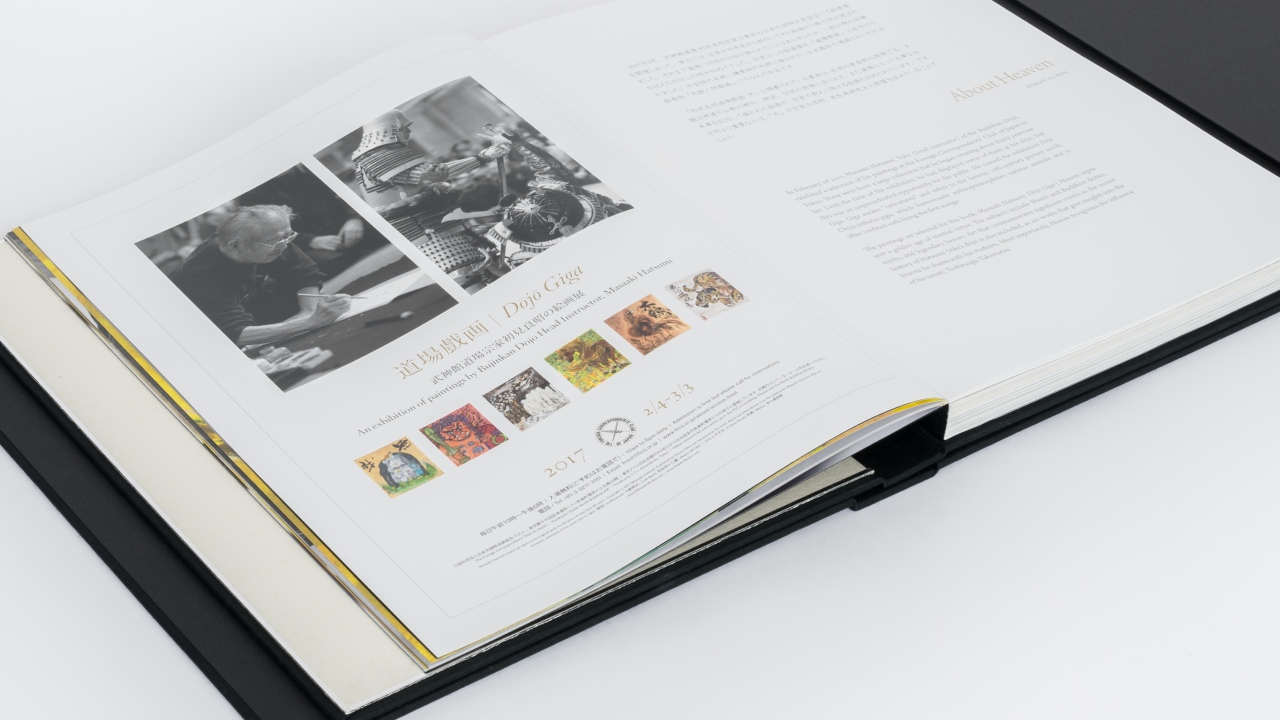

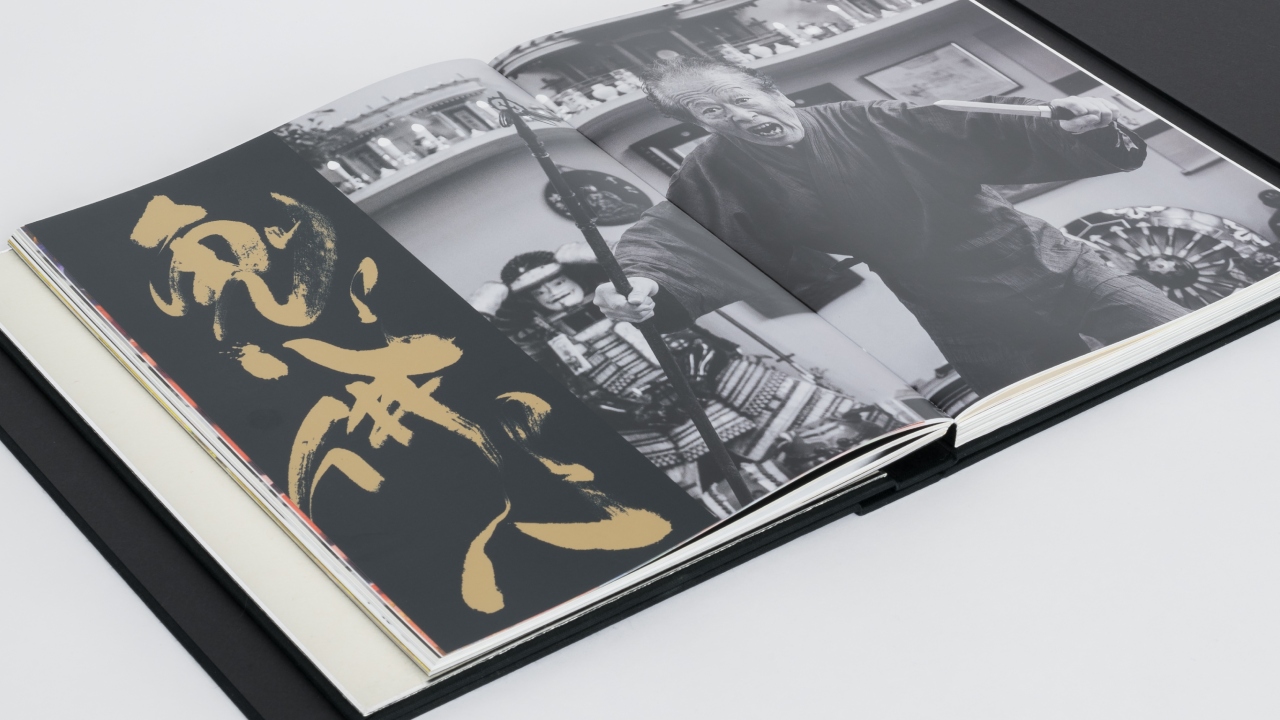

Masaaki Hatsumi: Dojo Giga | Heaven'

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

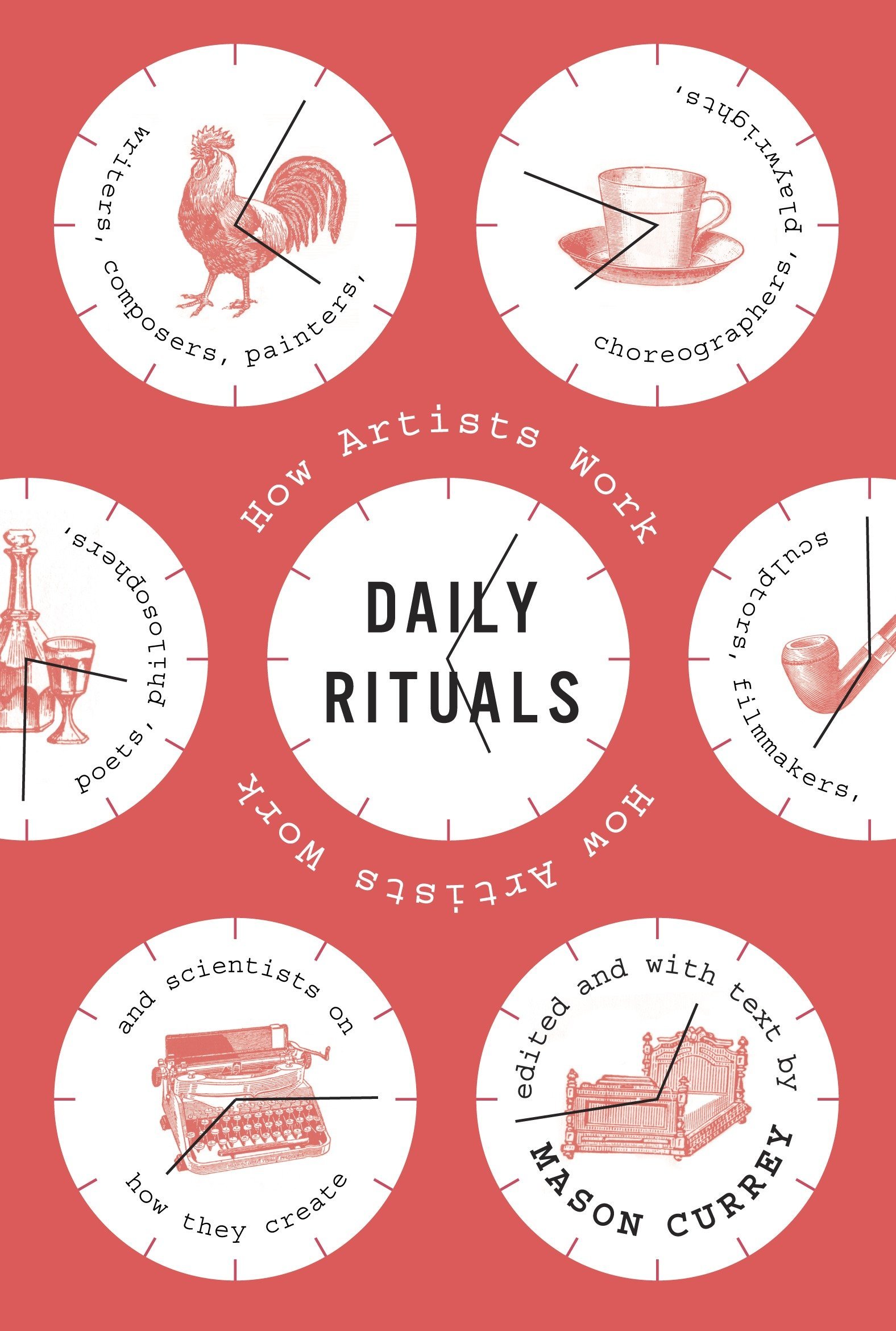

Daily Rituals: How Artists Work

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

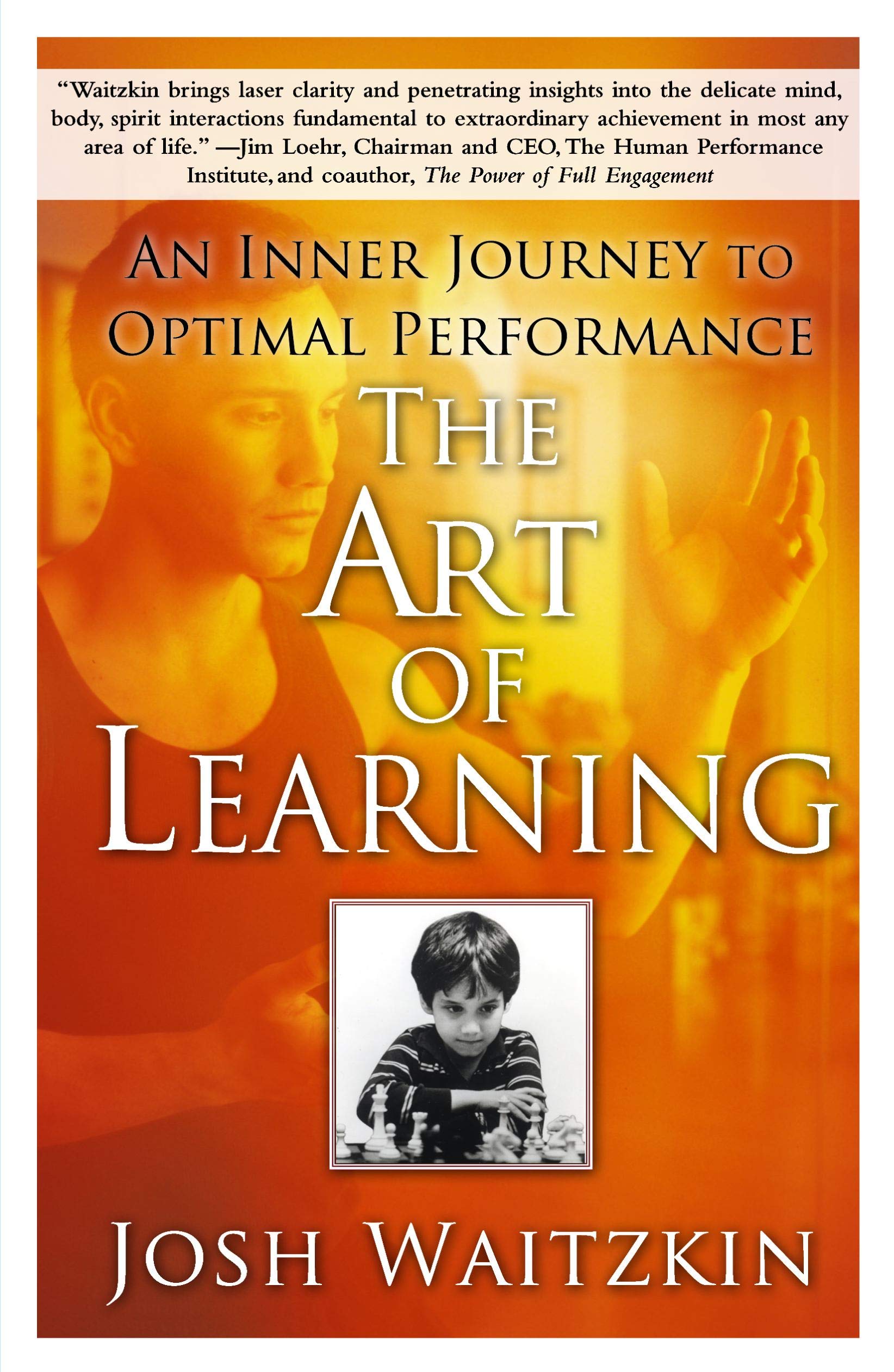

The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

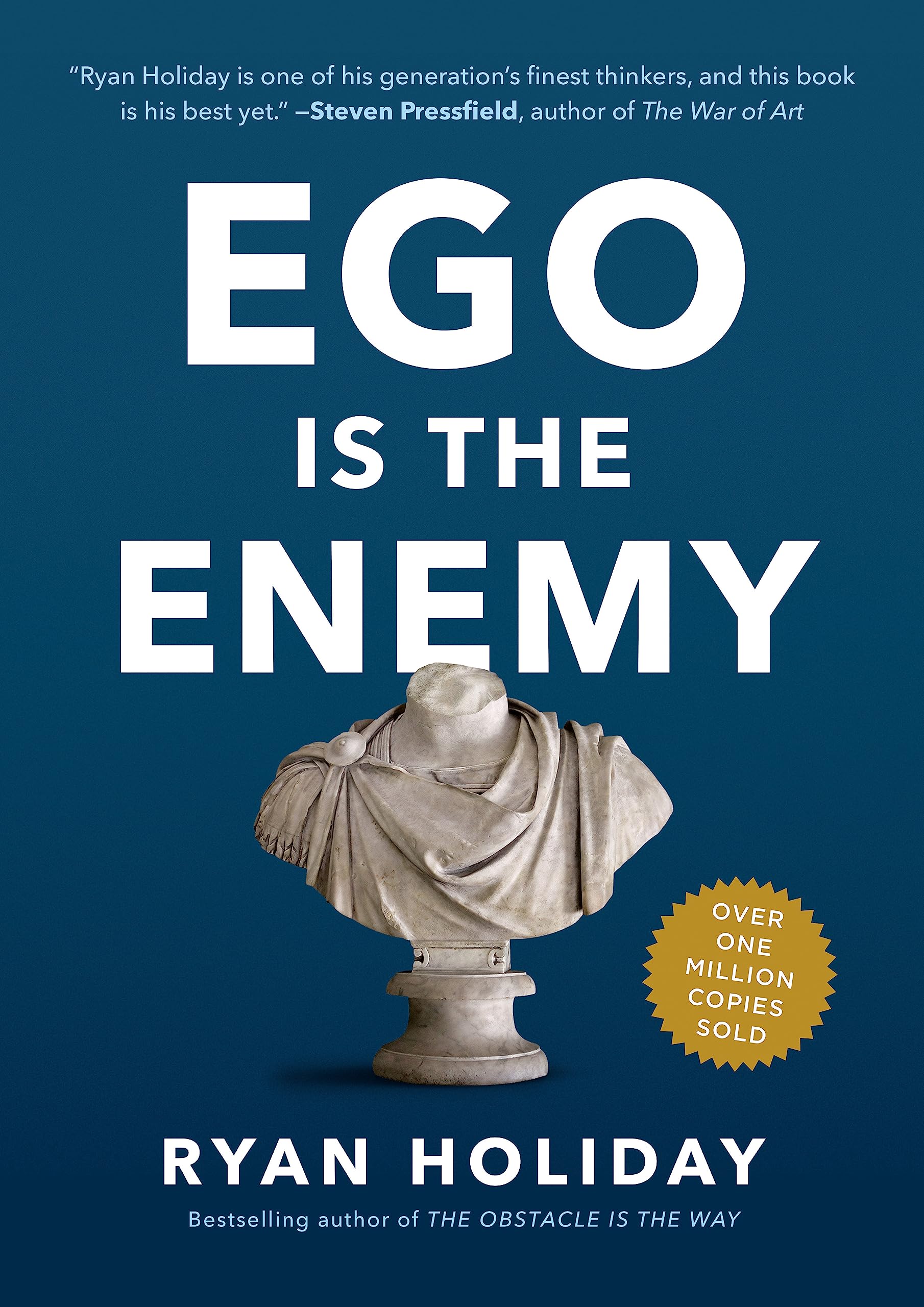

Ego Is the Enemy

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

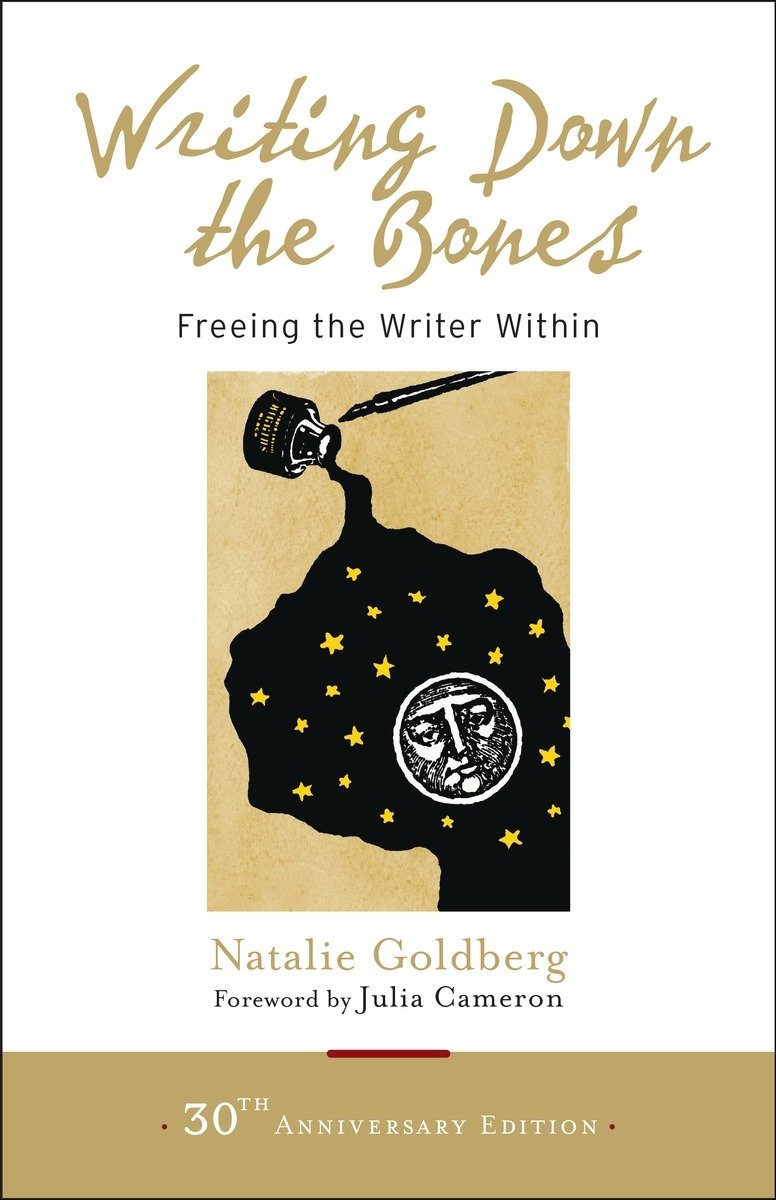

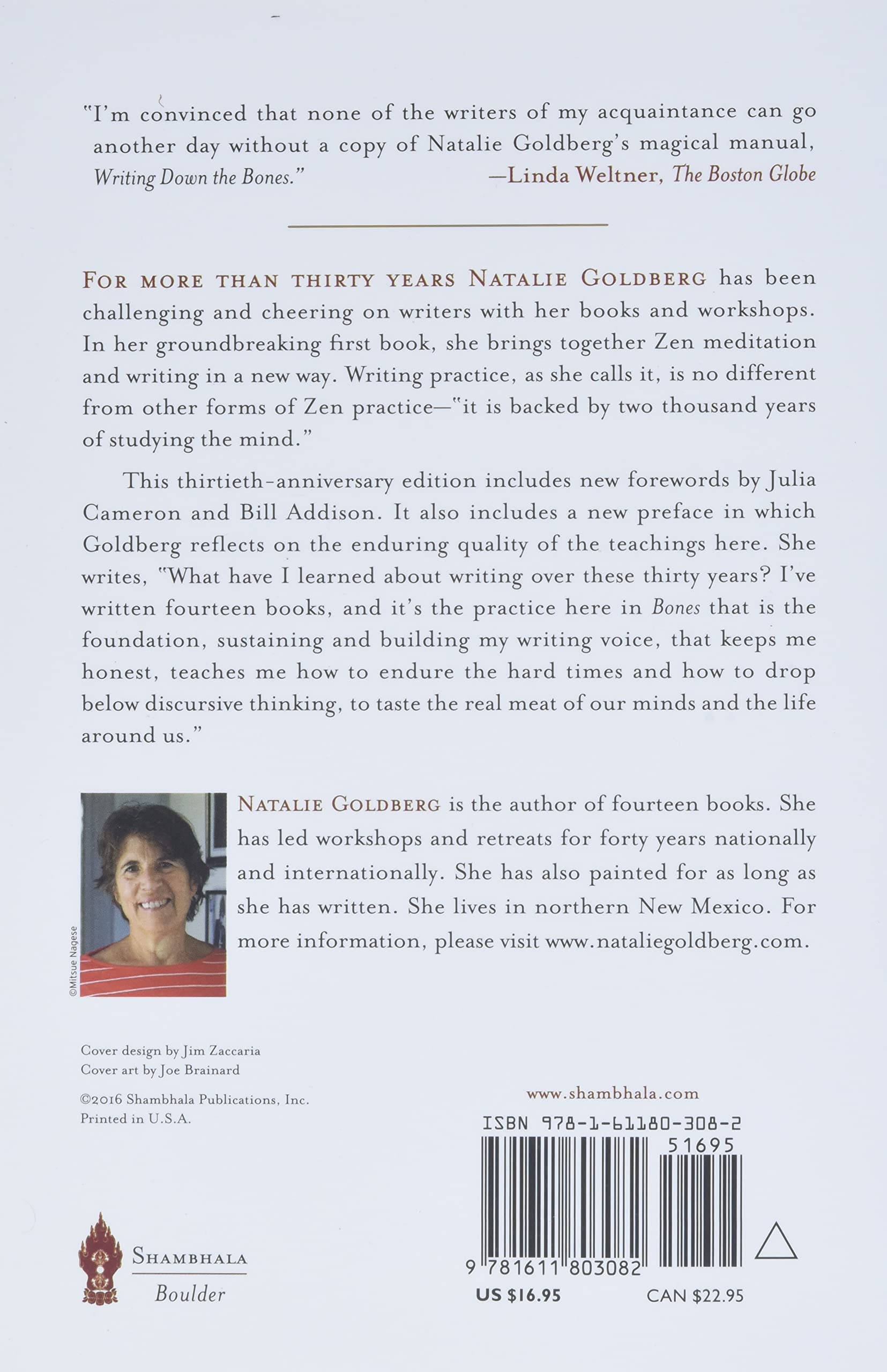

Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

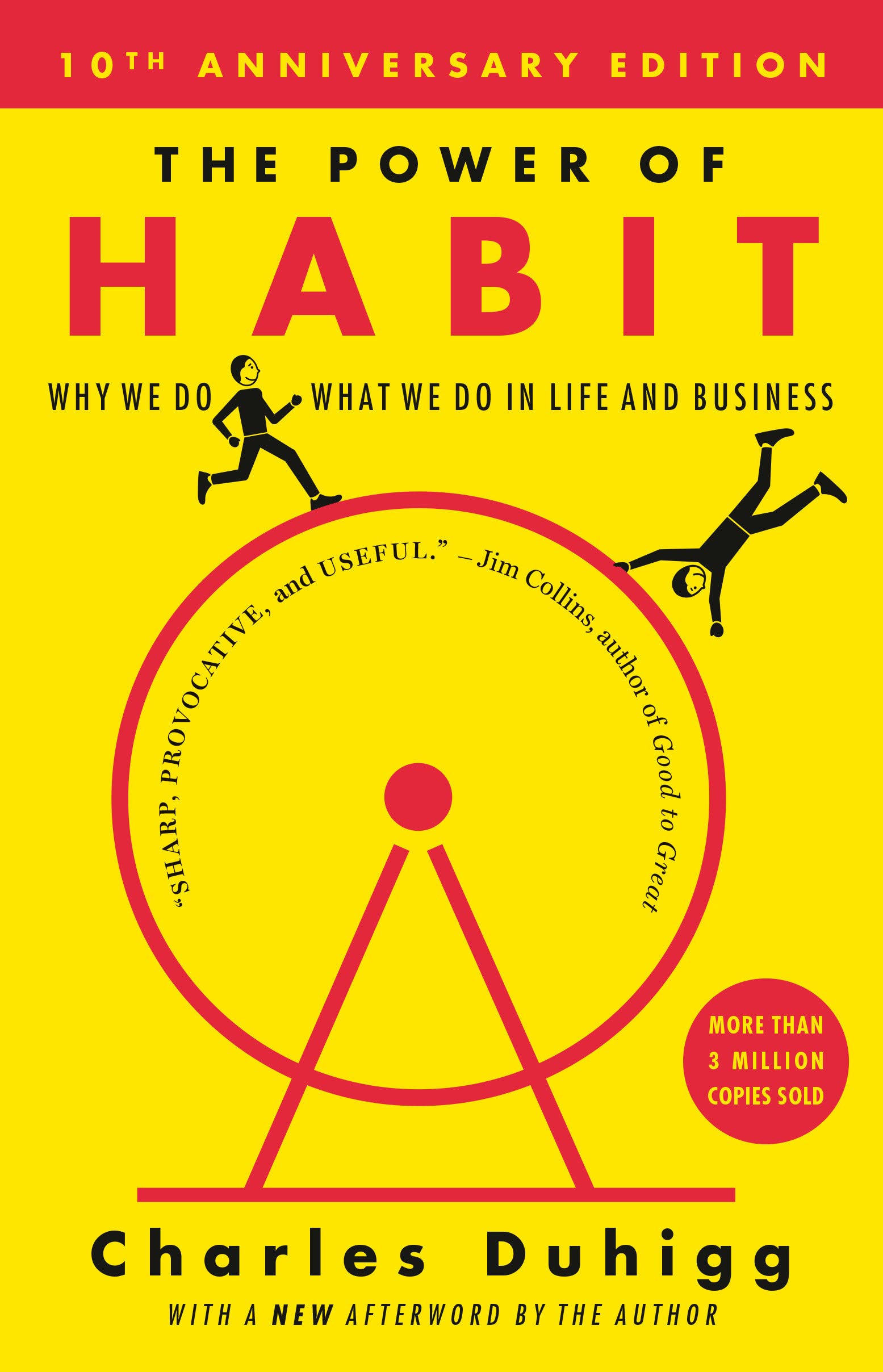

The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Magic of Thinking Big: (Vermilion Life Essentials)

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Loom of Language: An Approach to the Mastery of Many Languages

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Artist's Way Morning Pages Journal: Deluxe Edition

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Art of Memoir

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

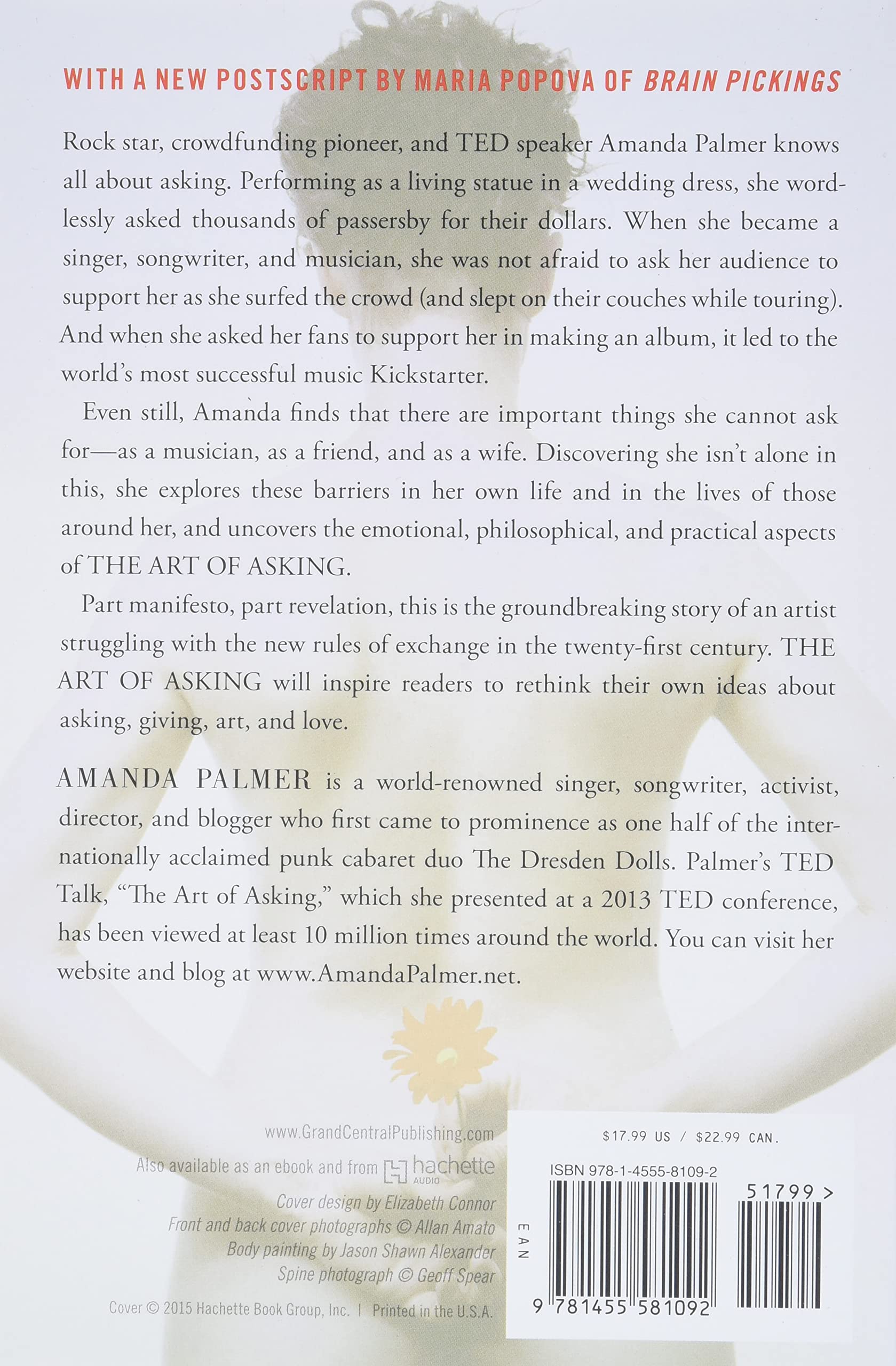

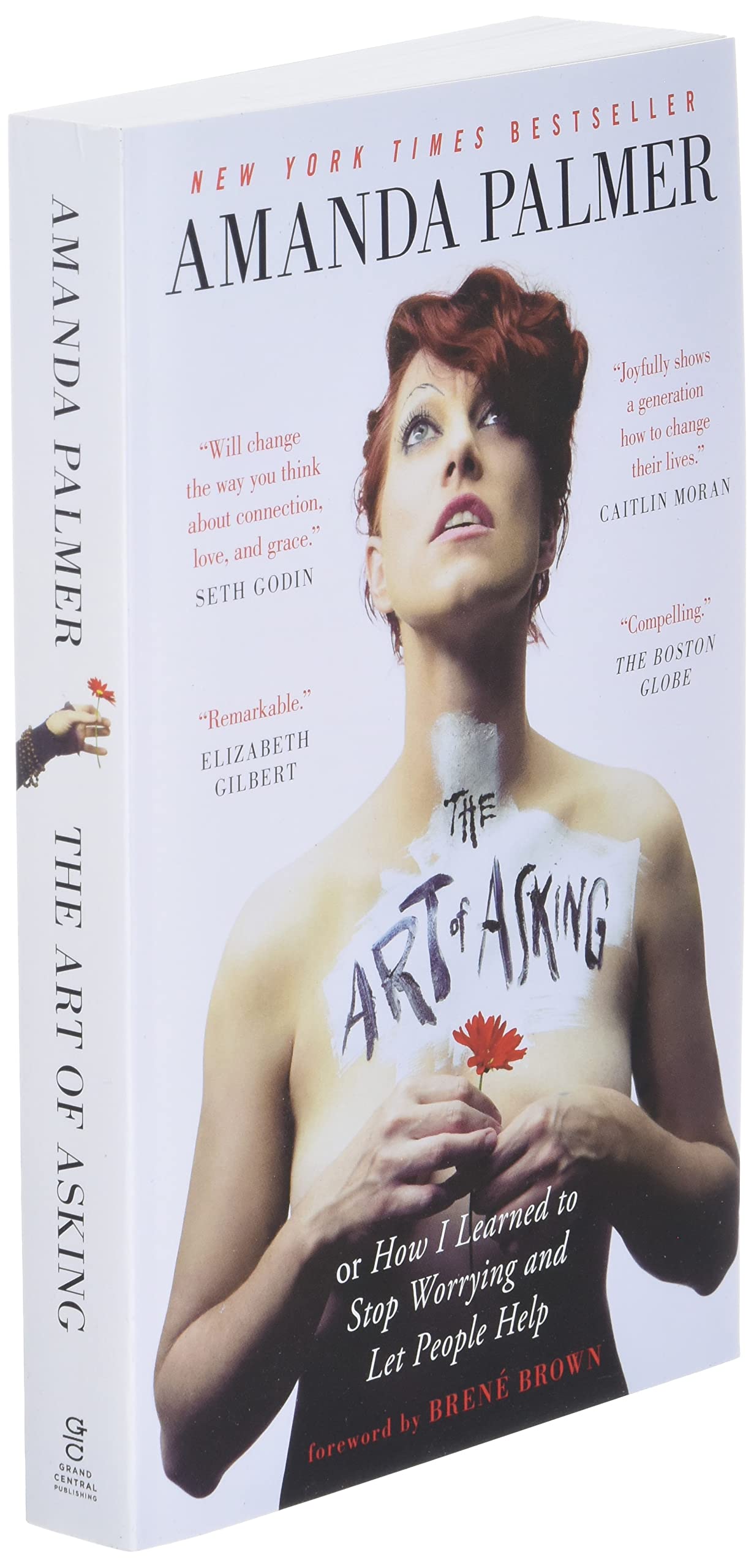

The Art of Asking: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Almanack of Naval Ravikant: A Guide to Wealth and Happiness

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Simple & Direct

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Save The Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Play It Away: A Workaholic's Cure for Anxiety

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Play for a Living

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (A Memoir of the Craft (Reissue))

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-Term Fulfillment

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Joy On Demand

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

How to Stop Worrying and Start Living

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Extreme Ownership

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Emergency: This Book Will Save Your Life

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Already Free: Buddhism Meets Psychotherapy on the Path of Liberation

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

10% Happier Revised Edition: How I Tamed the Voice in My Head

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

The Art of Possibility: Transforming Professional and Personal Life

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Foundation Korean (Michel Thomas Method) Audiobook

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please delete

Talk To Me In Korean Level 1 (Downloadable Audio Files Included) (English and Korean Edition)

Are you sure you want to delete this listing?

All related data including comments will be permanently deleted.

Yes, please deletePersonal growth is a lifelong journey. These titles have offered Ferriss valuable insights, strategies, and perspectives on bettering oneself.

Self-Improvement Books

Are you sure you want to delete this list?

All related data including ALL ASSOCIATED LISTINGS will be permanently deleted!

Yes, please delete